Table of Contents

The Ultimate Manual for Urban Kenyan Farmers: Growing Dwarf Papayas in Pots

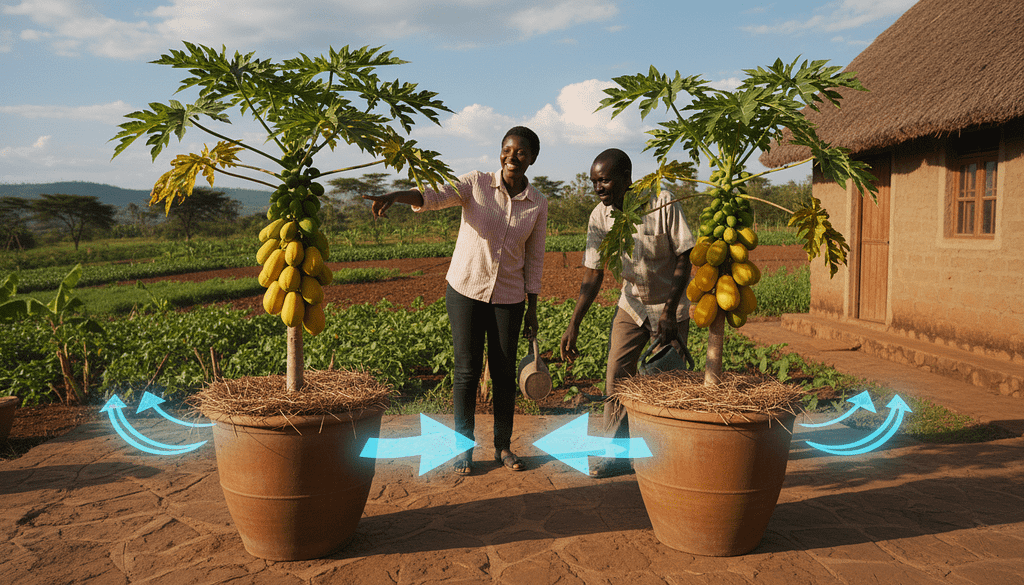

Farming in Kenya is currently undergoing a radical transformation, shifting from the traditional, vast acres of the Rift Valley and Central Highlands to the concrete jungles of our growing cities. From the windy balconies of Kilimani apartments to the sun-drenched rooftops of Mombasa and the compact backyards of Kisumu, urban agriculture is taking root. One of the most lucrative, visually stunning, and satisfying crops to spearhead this urban farming revolution is the Dwarf Papaya. Unlike the towering indigenous varieties that require massive root space, deep soils, and years to mature, modern dwarf hybrids are genetically engineered to remain compact often growing no taller than 2 meters. This compact nature makes them the perfect candidate for container gardening, allowing city dwellers to bypass land constraints entirely.

For the beginner farmer facing land constraints, growing dwarf papaya in containers represents a low-entry barrier to high-value agriculture. It offers fresh, organic fruit for the family and a potential income stream by selling to neighbors or local *mama mbogas*. In the current Kenyan market, where food inflation is a genuine concern, a single large, sweet papaya can fetch between KES 100 and KES 200 depending on the season and location.

Read more

How to Start Bulb Onion Farming in Kenya: Complete 2026 Guide, Costs & Profit Per Acre

A well-maintained container tree, if fed correctly, can produce 30 to 50 fruits per season. This translates to significant household savings or a tidy profit margin, all generated from a few square feet of unused balcony space.

However, achieving these massive yields in a container is not accidental; it requires a deep understanding of the specific physiological needs of the *Carica papaya* plant when its root system is confined. The “container environment” presents unique challenges regarding moisture retention, temperature fluctuation, and nutrient availability that differ vastly from open-field farming in places like Meru or Machakos. In the open ground, roots can travel meters to find water; in a container, the plant is entirely dependent on you. If you miss a watering cycle during the dry January heat, the plant suffers immediately. Therefore, mastering the soil mix and irrigation schedule is the difference between a yellowing, stunted plant and a lush, fruit-bearing tree.

—

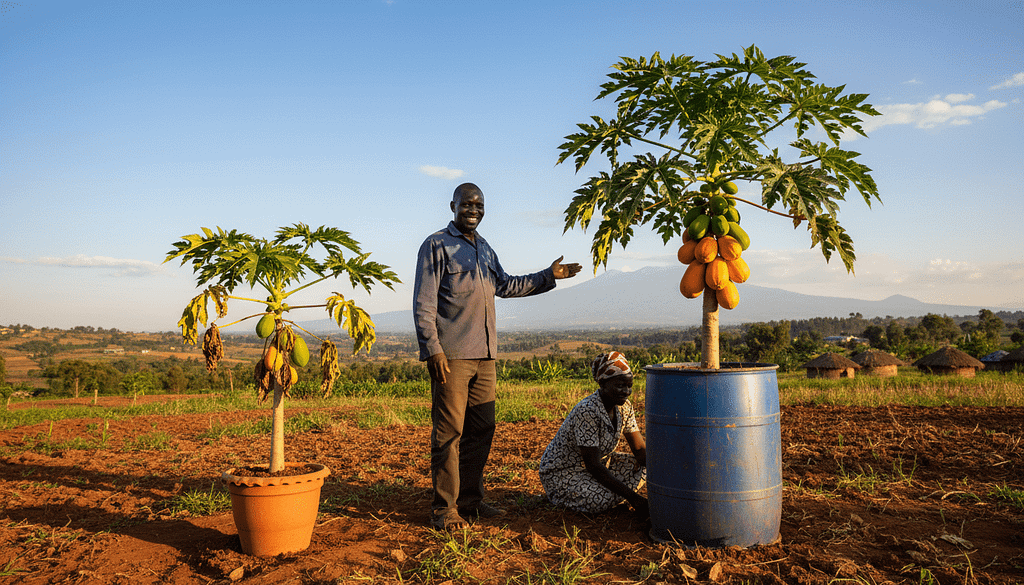

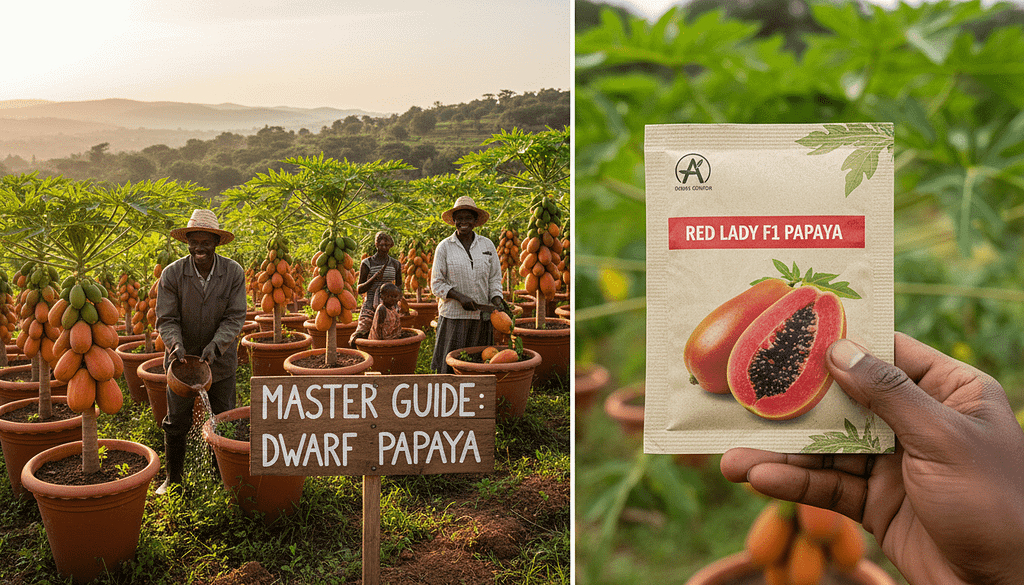

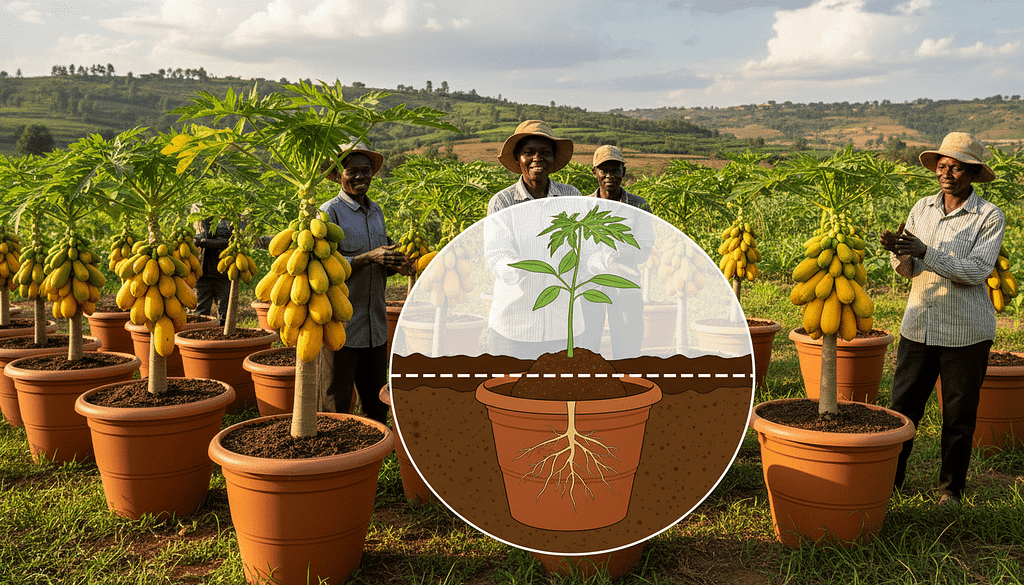

Step 1: Selecting the Perfect Container

The size and material of your container are the first determinants of your papaya’s potential size, health, and lifespan. A papaya tree, even a dwarf hybrid, is a heavy feeder with a rigorous fibrous root system that demands significant volume to anchor the plant and forage for nutrients. Many beginners make the fatal mistake of using standard 10 or 20-liter flower pots commonly sold along Ngong Road or highway nurseries. These are far too small. The roots will hit the walls of the pot within three months, become “root-bound,” and the plant will stunt, refusing to flower or fruit.

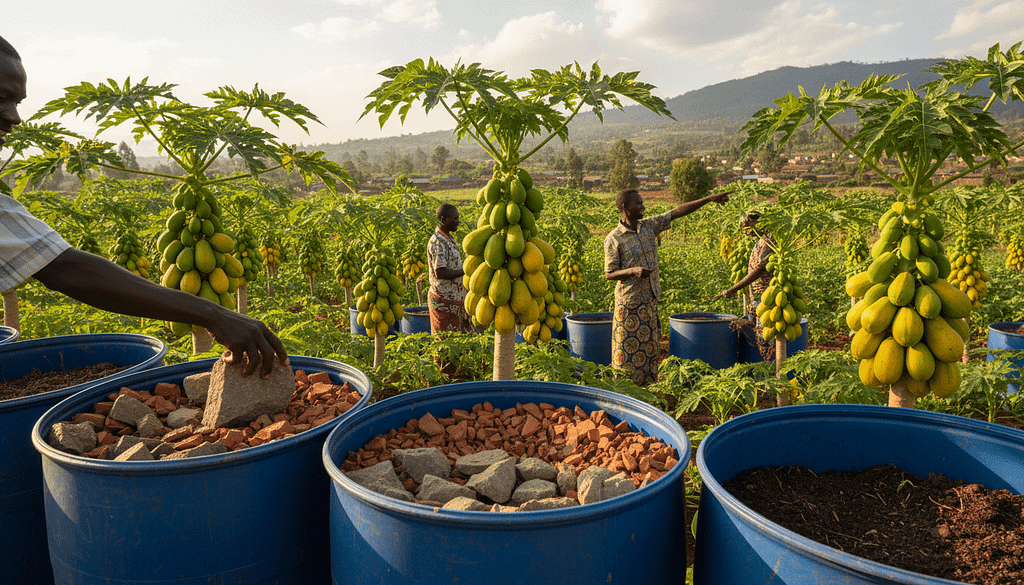

You need a container with a volume of at least 60 to 100 liters to guarantee a full harvest. The most cost-effective and durable solution for many Kenyan farmers is recycling blue plastic industrial drums. These drums are ubiquitous in industrial areas and hardware stores. Cutting a standard 200-liter drum in half horizontally provides two excellent 100-liter pots. Plastic is preferred over clay (terracotta) for papaya because clay is porous and wicks moisture away from the soil too fast in the hot African sun, whereas plastic retains moisture, which papaya roots crave.

Safety is paramount when repurposing industrial containers. If you are buying used drums, you must ensure they are thoroughly washed and decontaminated. Ideally, source drums that were used for food products (like glucose, juice concentrate, or cooking oil) or mild detergents, rather than heavy industrial chemicals or petroleum products. Scrub the interior with soapy water and bleach, and let them sit in the sun for two days. This ensures that no toxic residue leaches into the soil and enters the fruit you intend to eat.

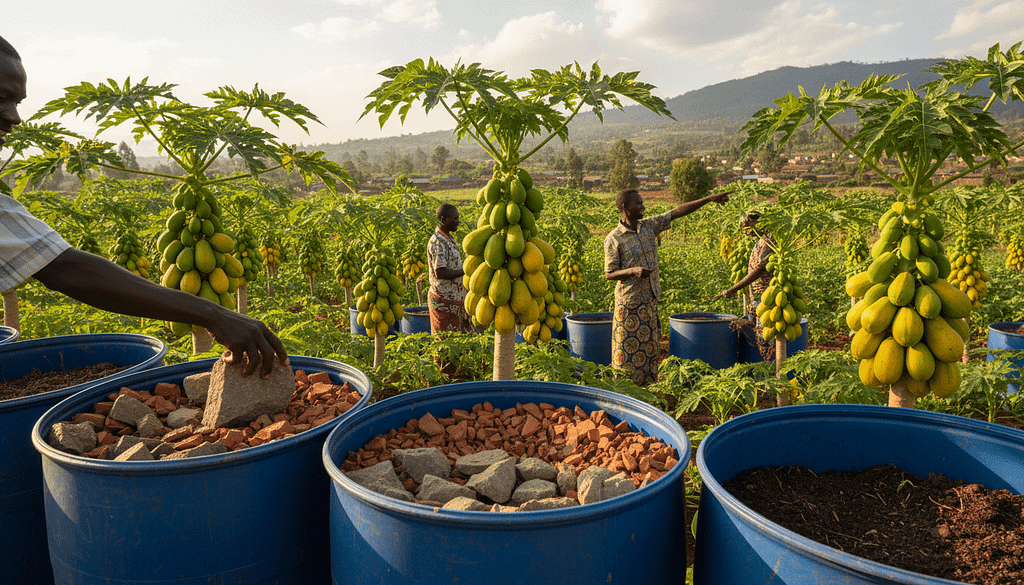

Drainage is the single most critical technical aspect of container preparation because papaya roots are notoriously susceptible to “wet feet” or root rot (Phytophthora). Unlike rice or arrowroots, papaya roots need oxygen as much as they need water. If water sits at the bottom of the drum for even 48 hours, the roots will rot, turning mushy and black, and the tree will die. You must drill or cut at least 8 to 10 holes, each about the size of a shilling coin, at the bottom and the lower sides of the container.

Once the holes are drilled, do not just dump soil in. You must create a “drainage layer.” Place a 2-inch layer of large gravel, broken clay pot pieces (crocks), or medium-sized stones at the very bottom of the drum. This physical barrier ensures that even if the soil compacts over time, the drainage holes will not get clogged with mud. During the heavy long rains in April, this layer allows excess water to escape freely, saving your plant from drowning.

Finally, consider the placement mechanics. Never place your container directly on flat concrete or tiles without elevating it slightly. If the drainage holes are flush with the ground, a vacuum seal can form, preventing water from draining out, or the water can pool around the base, damaging your patio. Place the drum on three or four bricks or a custom metal stand. This airflow under the pot also helps “air-prune” the roots at the bottom, preventing them from circling endlessly and keeping the root system healthy.

Step 2: The “Magic” Soil Mix for Kenyan Climate

Garden soil alone is the enemy of container gardening. If you dig up red soil from a shamba and put it in a pot, it will compact into a concrete-like brick after a few waterings. This suffocation prevents roots from expanding and accessing nutrients. For dwarf papayas, you need a potting mix that is friable (crumbly), nutrient-dense, and exceptionally free-draining. The goal is to mimic the forest floor—rich in organic matter but loose enough for water to pass through instantly.

The ideal formula for the Kenyan climate—balancing moisture retention for the dry season and drainage for the wet season—is a 2:1:1 ratio. This translates to 2 parts Topsoil (preferably loamy forest soil or garden center soil), 1 part well-decomposed Manure (cow or goat manure is superior to chicken manure for bulk volume), and 1 part Coarse Sand (river sand). Do not use ocean sand from the coast as it contains salt, which kills plants. The sand is the structural component that ensures drainage.

To supercharge this mix and ensure your tree has food for the first few crucial months, you should add amendments. Mix in a handful of Bone Meal per pot. Bone meal is rich in phosphorus, which is essential for strong root development in the early stages. Additionally, add Neem Cake powder. Neem cake is an organic fertilizer that also acts as a systemic pesticide, protecting the young roots from soil-borne nematodes, which are a common plague in many agricultural soils across Kenya.

Mixing is a physical process that requires attention. You must blend the topsoil, manure, and sand thoroughly until the color is uniform. If you leave pockets of pure manure, it might burn the roots; pockets of pure sand will hold no water. Use a shovel to turn the pile over multiple times. If the mixture feels too dry and dusty, sprinkle it with water as you mix to bind the dust and start the microbial activity in the manure.

Read more

How to Grow Coriander at Home Using Old Tyres: Easy Step-by-Step Guide

Once the mix is ready, fill your container but—and this is crucial—do not fill it to the brim. Leave about 4 to 6 inches of space from the rim. This space is known as “headspace.” It is essential for holding water during irrigation so it can soak down slowly rather than spilling over the sides immediately. It also allows space for you to add more compost or mulch later as the soil level naturally sinks over time.

Before you even think about planting, you must “water in” the pot. Water the soil in the drum thoroughly until water runs out of the bottom holes. This serves two purposes: first, it settles the soil and eliminates large air pockets that could dry out roots. Second, it flushes out any excess salts or acidity from the manure. Let the pot sit for a day or two after this initial watering before planting your seedling.

—

Step 3: Sourcing and Sowing Seeds

The genetic quality of your seed determines 80% of your success. You cannot cheat this step. In Kenya, the most popular, tested, and reliable dwarf variety is the Red Lady F1 Hybrid. This variety is an agricultural marvel: it is early maturing (producing fruit in 7-8 months), highly resistant to the Papaya Ring Spot Virus (a major destroyer of papaya in East Africa), and most importantly, it is a productive hermaphrodite. Other excellent varieties available in the Kenyan market include Sinta F1 and Calina IPB9.

Do not—under any circumstances—use seeds from a papaya you bought at the supermarket or *soko*. Supermarket papayas are usually F1 hybrids themselves. If you plant their seeds (the F2 generation), the offspring will be genetically unstable. You will likely end up with tall, male trees that bear no fruit, or trees with tiny, unsweet fruits. You will have wasted 8 months of water and effort on a tree that gives you nothing. Invest the KES 800 – 1,500 for a certified seed packet; it pays for itself with the first two fruits harvested.

To maximize germination, treat your seeds like royalty. Papaya seeds have a hard, dark coating that can delay sprouting. Soak your seeds in lukewarm water for 24 hours before planting. This softens the shell. For even better results, you can add a pinch of fungicide or even a drop of hydrogen peroxide to the water to kill any surface mold. If any seeds float after 24 hours, discard them—they are likely empty and will not grow.

It is highly recommended to start your seeds in a nursery setup rather than sowing directly into the large 100-liter drum. A small environment allows you to control humidity and temperature better. Use a plastic seedling tray or small polythene planting bags (4×6 inches). Fill them with a light starting mix—Cocopeat (coconut fiber dust) is excellent and widely available in Kenya. It is sterile and holds moisture perfectly. Sow 2 seeds per bag at a depth of roughly 1 centimeter.

Placement of your nursery is key. Keep the trays or bags in a warm area that receives bright but indirect light. Direct midday sun will cook the seeds in the black plastic. In the Kenyan climate, germination should occur within 2 to 3 weeks. You will first see a tiny white loop emerging, which will straighten into a stem with two embryonic leaves (cotyledons). Keep the soil consistently moist—like a squeezed-out sponge—but not dripping wet.

Once the seedlings reach about 15cm tall (roughly 6 weeks old) and have several sets of “true leaves” (leaves that look like papaya leaves), they are ready for selection. If both seeds in your bag germinated, you must be ruthless. Choose the strongest, thickest, and shortest seedling. Snipping off the weaker one ensures the survivor gets all the resources. Do not pull the weak one out, as this might damage the roots of the winner; simply cut it at the soil line with scissors.

—

Step 4: Transplanting and Location

Transplanting is a surgical procedure for plants. Papayas are notoriously sensitive to root disturbance. If the root ball breaks or crumbles during the move, the plant may go into “transplant shock,” halting growth for weeks or even dying. To transplant safely, water your seedling thoroughly one hour before moving it. This binds the soil together, keeping the root ball intact.

Dig a hole in the center of your large container that is slightly larger and deeper than the root ball of the seedling. The depth is critical. You must plant the seedling at the exact same depth it was growing in the nursery bag. If you bury the stem deeper, the moisture in the soil will rot the soft stem (collar rot). If you plant it too shallow, the upper roots will be exposed to the hot sun and dry out.

The actual move requires gentle hands. Cut the plastic nursery bag down the side with a razor blade or knife. Gently peel the plastic away rather than trying to shake the plant out. Support the bottom of the root ball with your hand and lower it into the hole in the drum. Backfill with your soil mix and gently press down with your fingers to remove air pockets. Do not stomp or press too hard, as this compacts the soil.

Timing is everything in Kenya. Perform this transplanting operation in the late afternoon, ideally after 4:00 PM or on a cloudy day. By transplanting when the sun is going down, you give the plant 12 hours of cool darkness to recover and establish water connections before it has to face the intense heat of the next day. Immediately after planting, water the area around the stem gently.

Positioning your container is the next vital step. Papayas are sun-worshipers. They are tropical plants that convert sunlight directly into sugar. They require 6 to 8 hours of direct sunlight daily. In Nairobi or the highlands, a north-facing wall is often ideal as it captures the most sun as it moves across the sky. If you put them in the shade, the tree will grow tall and spindly (etiolated) seeking light, and will produce little to no fruit.

Wind is a hidden enemy. Papaya stems are hollow and succulent. While they can bend, strong gusts—common in areas like Kitengela, Rongai, or coastal beachfronts—can snap the tree or shred the large leaves. If you are in a windy area, place the container near a wall or windbreak. Additionally, because the fruit load is heavy, a strong wind can blow a top-heavy container over. Ensure your container is stable on its brick base.

—

H2: Step 5: Fertilization and Water Management

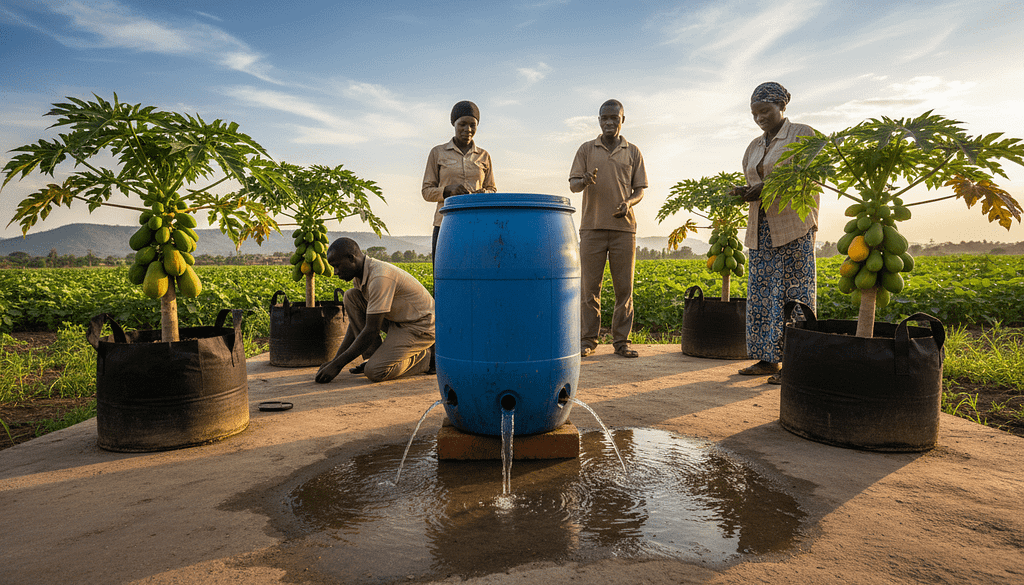

Papayas are thirsty plants. Their large leaves have a high surface area for transpiration (water loss). In the hot months (January through March), you may need to water your container every single day. However, guessing is dangerous. The rule of thumb is the “Finger Test”: Stick your index finger into the soil up to the second knuckle (about 2 inches deep). If it feels dry, water immediately. If it feels damp or cool, wait.

Mulching is not optional in Kenya; it is mandatory. The African sun hitting the side of a plastic drum can heat the soil to dangerous levels, cooking the roots. You must apply a thick layer (3-4 inches) of organic mulch on top of the soil. Use dry grass, sugarcane bagasse, or rice husks (common in Mwea). This blanket keeps the soil cool, prevents water from evaporating, and suppresses weeds. As it rots, it adds organic food to the soil.

When you water, technique matters. Always water at the base of the plant, directly onto the mulch or soil. Never shower the leaves. Wet leaves, especially in the evening, invite fungal diseases like Powdery Mildew and Anthracnose, which are prevalent during the cold, damp months of June and July (“Baridi” season). Keep the foliage dry to keep the plant healthy.

For massive harvests, you must follow a strict feeding schedule. A container plant cannot send roots out to find food; you must bring the food to it.**Vegetative Stage (Month 1-3):** The plant needs Nitrogen to build its green factory (leaves and trunk). Apply a nitrogen-rich fertilizer like **CAN (Calcium Ammonium Nitrate)** or well-rotted chicken manure every 4 weeks. A handful of manure or a tablespoon of CAN is sufficient.**Flowering/Fruiting Stage (Month 4 onwards):** The needs shift. Too much nitrogen now will make leaves, not fruit. Switch to a high-potassium and phosphorus fertilizer. Use **NPK 17:17:17** or **Murate of Potash**. Potassium is the “sweetener” for the fruit and helps the plant support the heavy load.

Micronutrients are the secret weapon. Kenyan soils are often deficient in Boron and Zinc. Boron deficiency causes “bumpy” or deformed fruit (a condition where the papaya looks lumpy like a gourd). Once a month, spray a foliar fertilizer rich in trace elements. Products like *EasyGro* or *Osho* foliar feeds are readily available in agro-vets. Spray this on the underside of leaves early in the morning for best absorption.

Critical Warning: When applying granular chemical fertilizers, never place them directly against the stem. They are concentrated salts and will chemically burn the plant tissue, causing the stem to rot and snap. Sprinkle the fertilizer in a ring around the extreme edge of the container, as far from the stem as possible, then water it in immediately to dissolve it.

—

Step 6: Pest and Disease Control

Container gardening reduces some pest risks, but not all. In the urban Kenyan environment, the biggest enemies are Spider Mites and Mealybugs.**Spider Mites:** These are microscopic pests that thrive in dry, dusty weather. They look like moving red dust. They suck the chlorophyll from leaves, causing yellow stippling or a “sandblasted” look. If you see fine webbing between leaves, you have a severe infestation.**Mealybugs:** These appear as white, cotton-like fluffy masses on the stem and under leaves. They suck sap and secrete a sticky “honeydew” that attracts ants and causes black sooty mold.

For organic control, which is best for home gardens, use a mixture of Neem Oil and soap. Mix 1 tablespoon of Neem Oil and 1 teaspoon of liquid dish soap (like sunlight liquid) in 1 liter of warm water. Shake vigorously. Spray the plant thoroughly, focusing heavily on the undersides of the leaves where these pests hide. Repeat this every 7 days. The soap breaks the pest’s shell, and the Neem disrupts their breeding.

Viruses are the silent killers. The Papaya Ring Spot Virus (PRSV) is incurable. It is characterized by dark green “oil spots” or rings on the fruit, and yellow mosaic patterns on distorted leaves. If you see a tree with these symptoms, you must be brave: uproot it and burn it or bag it for trash immediately. Do not compost it. If you leave it, aphids will carry the virus to your healthy trees. Growing resistant varieties like Red Lady F1 is your best defense.

Fungal issues like Anthracnose cause sunken, water-soaked spots on the fruit that turn black and mushy as the fruit ripens. This is common during the rains. To prevent this, ensure good airflow around your containers. Do not crowd the pots together; leave at least 1 meter between drums. If you spot affected fruits or leaves, prune them off immediately with sterilized shears and bury them far away from the garden.

Critical Warning: Avoid spraying pesticides—even organic ones—when the flowers are open and bees are active. Although dwarf hybrids are self-pollinating, bees and other insects assist significantly in increasing the fruit set and quality. Spray in the late evening (dusk) when bees have returned to their hives.

—

Step 7: Harvesting the Massive Yield

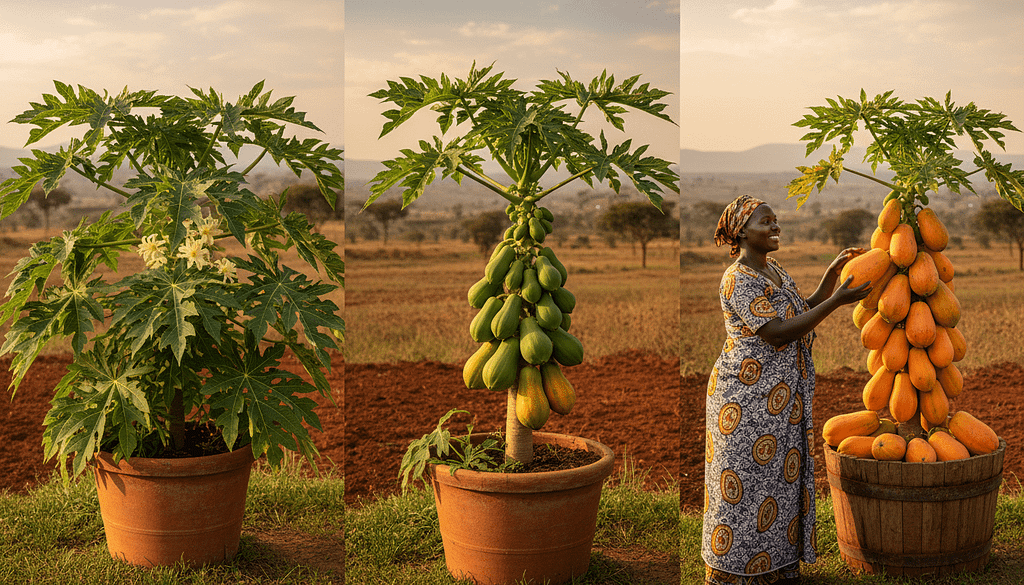

Patience is a virtue in farming. Dwarf papayas usually start flowering 4 to 5 months after transplanting. You will see small buds forming in the axils (where the leaf meets the stem). From flower to ripe fruit takes another 4 to 5 months. So, expect your first harvest roughly 8 to 9 months from seed. It is a long wait, but the yield is continuous once it starts.

The sign of maturity is a change in skin color. Do not harvest the fruit when it is solid dark green; it will be rubbery and tasteless. For the local market or home consumption, wait until the fruit skin changes from dark green to having yellow streaks running from the bottom upwards. This is called the “color break” stage (about 25-50% yellow). At this stage, the fruit has developed its full sugar content but is still firm enough to handle without bruising.

To harvest, hygiene and technique are important. Twist the fruit gently to snap it off the stem. If it resists, do not pull hard, or you might damage the main trunk or knock off the small, unripe fruits growing directly above it. Use a sharp knife or sanitized pruning shears to cut the peduncle (fruit stem) cleanly.

Critical Warning: When you cut the fruit, a white milky sap (latex) will ooze from the stem. This latex contains papain, an enzyme that digests protein. It can be very irritating to the skin and dangerous if it gets in your eyes. Always wear long sleeves or wash your hands immediately after harvesting. If latex gets on the fruit skin, wipe it off, as it can burn the skin of the fruit and leave ugly brown marks.

After harvesting, store the papayas at room temperature on a kitchen counter or in a crate cushioned with newspaper to finish ripening. Do not refrigerate them until they are fully ripe (soft to the touch and fully orange/yellow). Cold temperatures stop the ripening process permanently. A healthy dwarf tree in a container can produce fruit continuously for 2 to 3 years if well fed. However, after the third year, yields usually drop, and the tree may get too tall. It is best to start new seedlings when your current trees are 2 years old to ensure a continuous supply.

Where to Buy Papaya Seeds Online in Kenya

Buying genuine F1 hybrid papaya seeds is critical. Avoid unbranded seeds sold in open markets. They are often mixed or fake and lead to losses.

Trusted Papaya Seed Suppliers in Kenya

Kenya Seed Company

Reliable, certified seeds backed by government quality control.

👉 https://www.kenyaseed.com

Best for: Reliability and affordability

Royal Seed (Kenya Highland Seed / Simlaw Seeds)

Official distributors of Red Lady F1 Papaya, a top commercial variety.

👉 https://www.simlaw.co.ke

Best for: High-yield commercial papaya farming

Syngenta Kenya

Premium hybrid seeds with strong pest and disease resistance.

👉 https://www.syngenta.co.ke

Best for: Serious commercial and export-focused farmers

M-Shamba / iShamba Platforms

Connects farmers to verified agro-vets and seed suppliers via mobile and app.

👉 https://www.ishamba.com

Best for: Farmers outside major towns

Continental Seeds

Hybrid seeds adapted for East African conditions.

👉 https://continentalseeds.com

Best for: Dry and medium rainfall regions

Papaya Seed Prices in Kenya

- 10g F1 Hybrid packet (50–70 seeds): KES 800 – 1,500

- Germination rate: 85–95% with genuine seeds

- Value: High ROI despite higher upfront cost

⚠️ Always confirm the stockist before paying. Ask for certification and receipts.

Comprehensive FAQ

Q1: Can I grow papaya from the seeds of the fruit I ate?

A: It is not recommended. Fruits from supermarkets are often hybrids. If you plant their seeds, the offspring will vary wildly—most will be male (non-fruiting) or very tall with poor fruit quality. Always buy Certified F1 seeds for containers.

Q2: How many years does a dwarf papaya tree live?

A: A papaya tree can live for 5-10 years, but for farming purposes, it is economically viable for only 3 years. After year 3, the fruit size decreases, the tree gets too tall for the pot, and it becomes more susceptible to diseases.

Q3: My papaya tree has flowers but they are falling off. Why?

A: This is called “flower drop.” It is a stress response. Common causes include extreme temperature fluctuations, irregular watering (letting the soil get bone dry then flooding it), or a lack of Boron. Ensure consistent moisture and apply a micronutrient foliar spray.

Q4: How much space do I need for one pot?

A: You need about 1.5 to 2 square meters per pot. This allows sunlight to reach the lower leaves and gives you enough space to walk around the plant to check for pests and harvest fruit without damaging the leaves.

Q5: Can I grow papaya indoors in Kenya?

A: Generally, no. Papayas need high intensity UV light that regular indoor bulbs or window light cannot provide. They will grow tall and weak. You can only grow them indoors if you have a glass atrium or greenhouse roof that lets in 6+ hours of direct sun.

Q6: What is the best season to plant papaya in Kenya?

A: You can plant year-round in containers if you have a reliable water source. However, planting roughly a month before the long rains (March) or short rains (October) helps the young seedlings establish with higher humidity and natural soft rain, reducing your workload.

Q7: Why are the leaves of my papaya turning yellow?

A: Context matters. If the very bottom leaves are yellowing and falling off, this is normal aging. However, if top or middle leaves turn yellow, it could be Nitrogen deficiency (add manure/CAN), Overwatering (check drainage), or Spider Mites (check undersides of leaves).

Q8: Can I use 100% manure in the pot?

A: NO! Pure manure is too strong and will burn the roots (ammonia burn). It also holds too much water, leading to rot. Always stick to the 2:1:1 ratio (Soil:Manure:Sand) to dilute the manure to safe levels.

Q9: Can I plant other crops in the same pot with the papaya?

A: It is not advised. The papaya has a shallow, aggressive root system that fills the pot. Planting vegetables at the base will cause competition for nutrients. However, you can plant shallow-rooted herbs like coriander (dhania) or mint purely as a living mulch, provided you increase the fertilizer and water slightly.

—

Conclusion

Growing dwarf papaya trees in containers is one of the most rewarding agricultural ventures for the modern Kenyan farmer. It requires minimal space but delivers maximum returns in terms of nutrition, aesthetics, and potential income. By choosing the right genetics (F1 Hybrids), mastering the drainage and soil mix, and maintaining a disciplined watering and fertilizing schedule, you can turn a barren concrete slab into a lush, fruit-bearing oasis.

Remember, patience is key. Farming is not magic; it is a science. Start with one or two drums, learn the rhythm of the plant, and soon you will be harvesting sweet, sun-ripened papayas right from your doorstep. The journey from a tiny black seed to a laden tree is a masterclass in nature’s abundance, available to anyone willing to get their hands dirty.

✔ Final Action Item: Visit your local Agro-vet this weekend, ask for “Red Lady F1” seeds, and find a recycled drum. Your farming journey begins now!

Read more

Watermelon Farming in Kenya 2026: Step by Step Guide from Planting to Harvest

Master Watermelon Farming in Kenya 2026 with this step-by-step guide. Learn about the best varieties (Sukari F1), cost of production, disease control, and how to make KES 300k+ per acre.

Urban Farming in Kenya: How to Grow Food in Small Spaces in Nairobi, Mombasa and Kisumu

Kisumu Urban farming in Kenya allows city residents to grow fresh food in balconies, rooftops, verandas and tiny plots, reducing food bills and improving nutrition in towns like Nairobi, Mombasa and Kisumu. With simple techniques such as containers, sack gardens and vertical farming, even renters in estates and informal settlements can start producing vegetables and…